The origin and development of millet farming were one of the most important economic foundations that underpinned the development of the Neolithic cultures of northern China and the early processes of social sophistication. The emergence and development of diversified modes of livelihood (modes of production and life) in the context of increasing transcontinental exchange during the Late Neolithic and Bronze Ages are also closely linked to the process of social sophistication. Western China was one of the key areas for the intensification and diffusion of millet farming and a pivotal area for prehistoric transcontinental exchange, and the process of spatial and temporal changes in agricultural development and livelihood patterns in the prehistoric period is a hot scientific issue of great interest.

Corn and millet were domesticated and utilized in northern China around 10,000 years ago, and 7,000-6,000 years ago corn and millet agriculture became the dominant form of livelihood in the east-central Loess Plateau. Before about 6,000 years ago the first people mainly cultivated millet, but after that they mainly used corn. Intensive millet farming emerged later in the western part of the Loess Plateau, with stable isotope data from bones from the Dadiwan site suggesting that millet farming intensified in the region around 5900 years ago. Due to the lack of direct dating evidence for millet remains, the timing and process of the shift in cultivation structure in the western Loess Plateau are unclear. During the Late Neolithic-Bronze Age, domestic livestock such as barley, wheat, cattle, and sheep, which originated in Southwest Asia, was introduced and gradually integrated into the biotechnological system of western China. The China Arc (i.e., the half-moon cultural diffusion belt) is a transcontinental exchange pivotal region, where the natural environment and cultural contexts vary significantly spatially, and the impact of prehistoric agricultural diffusion on the changing spatial and temporal patterns of ancestral livelihoods is unclear.

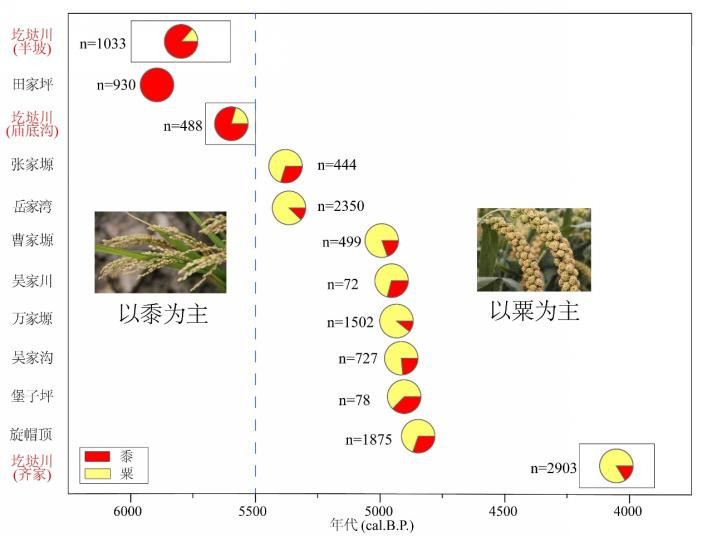

In response to these key questions, a team led by Associate Professor Ma Minmin from the College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lanzhou University, conducted research on plant and animal archaeology and skeletal stable isotope analysis in the western Loess Plateau and Yunnan Province, within the Arc of China. Based on in the western loess plateau Ge Da Chuan neolithic archaeological sites of carbon 14 dating and plant archaeological evidence, the team combined archaeological and paleoenvironmental evidence to systematically sort out the development and intensification of Neolithic millet agriculture and its influencing factors. The study shows that the first people of the Hanpo type of the Yangshao culture began to produce millet in the western part of the Loess Plateau as late as 6,100 years ago, and continued to do so until about 5,600 years ago. About 5,500 years ago, there was a shift from millet to corn, the main crop grown in dry farming on the western Loess Plateau (Fig. 1). As millet was significantly more productive than corn, this shift in cropping structure facilitated the subsequent growth and westward expansion of the millet farming population, and human subsistence pressures associated with climate change and population fluctuations are likely to have been an important cause of the change in cropping structure.

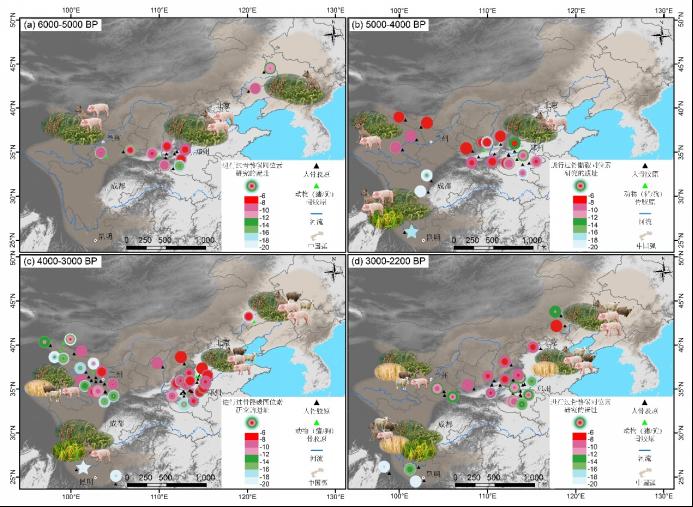

Based on the results of carbon 14 dating and carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of human and animal bones excavated from the Baiyangcun site in northwest Yunnan, and the upper Weihe River site, combined with published comparative studies on the archaeology of flora and fauna and carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of Neolithic-Bronze Age sites in Gansu and Qing, Sichuan and Yunnan, Yan and Liao, and the Central Plains, it was found that the spatial and temporal patterns of population occupation in the Late Neolithic-Bronze Age Chinese Arc varied significantly (Fig. 2). During the Late Neolithic (6,000-4,000 years ago), the ancestors of the Yan-Liao, Gan-Qing, and Central Plains regions had a predominantly C4recipe pattern, mainly growing corn and millet, supplemented by hunting and raising pigs and dogs. Agriculture emerged later in the Sichuan-Yunnan region, with the ancestors beginning to make extensive use of rice and millet of indigenous Chinese origin 5000-4000 years ago. Wheat, barley, and herbivorous livestock such as cattle and sheep were introduced and widely utilized in China between 4,000 and 2,200 years ago, but there was an asynchronous shift in the livelihood patterns of the people of the Chinese Arc and the Central Plains. In the Gan and Qing regions, wheat, barley, cattle, and sheep became important means of production for the ancestors 4,000-3,000 years ago, and wheat farming and cattle and sheep grazing became the dominant mode of subsistence by 3,000-2,200 years ago. However, in Yunnan and the Central Plains, wheat crops and cattle and sheep rearing were only supplementary modes of subsistence farming 4000-3000 years ago. The importance of wheat crops and herbivorous livestock in the subsistence pattern showed significant spatial variation between 3000 and 2200 years ago. During the Bronze Age, wheat and barley were rarely utilized by the ancestors of the Yan-Liao region. The asynchronous shift in the pattern of subsistence patterns is mainly related to the physiological characteristics of the exotic crops and livestock themselves, the natural environment of the exchange hub area, and the human subsistence pressures associated with climate change and population fluctuations.

These research efforts contribute to a deeper understanding of the development of prehistoric agriculture in western China and its impacts, providing new evidence for understanding the complex social environment of early societies, and are of great academic value in exploring the interactions between the survival strategies of prehistoric people, social development and environmental change.

The research results have recently been published in Frontiers in Plant Science, Quaternary Science Reviews, and Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

Related paper information:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.939340/full

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379122002967?via%3Dihub

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2022.905371/full

Fig. 1 Proportion of corn and millet remains from different periods at the Ohmengchuan site (red) and the Zhuanglang County survey site (black). n is the number of plant remains.

Fig. 2 Spatial and temporal distribution of recipes and livelihoods of people in the Late Neolithic-Bronze Age Chinese Arc and Central Plains.

δ13C: -12‰> dominated by C4foods, -18‰< dominated by C3foods, and between -18‰ and -12‰ consumed C3as well as C4foods.